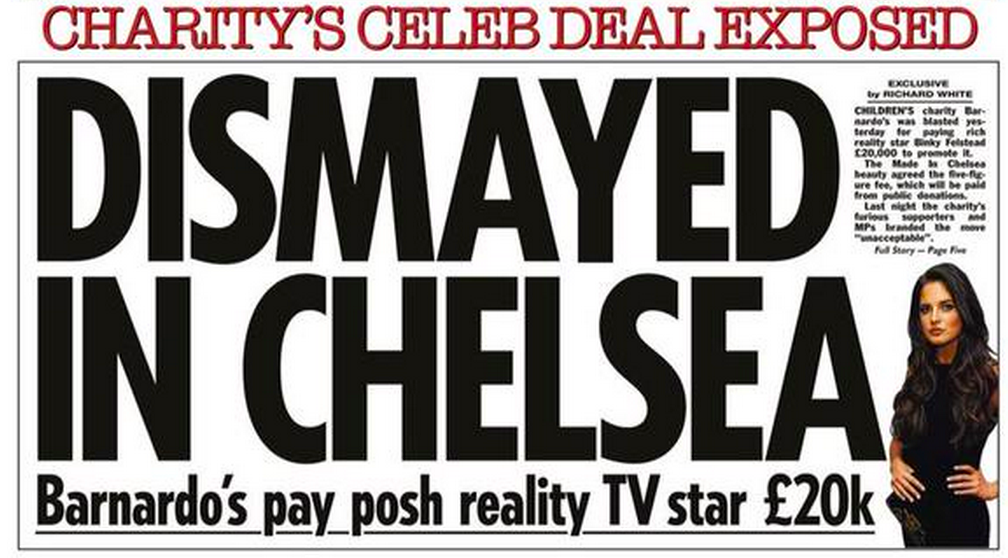

There was almost certainly a very sound commercial logic behind Barnados paying Made in Chelsea star Binky Felstead to endorse their retail campaign on social photo network Instagram. But the Sun splash yesterday and the social media outrage around it, highlights the complexity of modern charity fundraising and the need to plan ahead to manage those risks.

Credit to Barnados for the speed of their response in social media and their willingness to engage, though whether leading on the factual inaccuracy (they paid £3k, not £20k) was the best move, seems unclear.

.@TheSunNewspaper front pge incorrect. Our retail trading arm operates in commercial environment & is paying £3k for @BinkyFelstead campaign

— Barnardo’s (@barnardos) February 15, 2015

To small donors, individual fundraisers and charity supporters watching celebrities like Kirstie Allsopp pile into the debate on Twitter, any amount Barnado’s paid was bizarre. Surely celebrities should be queueing up, for free to be associated with charities?

https://twitter.com/PoppyD/status/567273740283949056

Barnardos paid Made in Chelsea star bet £3,000 and £20,000 to promote their charity shops. IT HAS JUST PUT ME OFF USING OR DONATING TO THEM

— eddie mchugh (@mrmgoo) February 16, 2015

https://twitter.com/Muzzerous/status/567396477207838721

Just wanted to confirm that I never intended to keep the fee from Barnardos & they have retained the full 3k according to my wishes. This ..

— Alexandra Felstead (@BinkyFelstead) February 16, 2015

Good for Binky in the end for waiving her fee, though the pain felt is likely to sting both for charity and celebrity for some time as the cost of small-scale fundraising increases and unpleasant associations and Google footprint linger.

In an exercise last year with a major charity, we helped simulate some of the outrage and hurt that the online community would feel and share via social media when the media spotlight shines on the reality of big charity influencing and recruitment strategy. The simple reality is that modern charities are complex organisations which need to do counter-intuitive things to achieve their aims. Most would prefer to actually achieve their social and charitable purposes rather than simply be seen to campaign for them – but the reality of effective public affairs, celebrity endorsement and senior staff recruitment all involve money, and plenty of it. As the saying goes, you have to speculate to accumulate.

Paradoxically, in a 140 character world, the best approach is not to shy away from complexity, but to articulate it clearly and give your supporters something to work with. Barnado’s replies to disappointed supporters on Facebook and Twitter did suggest a messaging strategy – in a nutshell: “we need more money so we can help more children” – but didn’t give many reasons to believe, nor did the statement. While it’s true that Twitter is an environment where many people shoot first and ask questions later, it can also be self-correcting to an extent, if the other side of the story emerges promptly and credibly enough (yesterday also saw rumours of children’s artist Tony Hart’s recent death debunked; he died in 2009). In this case, what kind of ROI has the charity seen from using paid endorsements for campaigns? Or in the case of lobbying: what policy changes have been achieved with a spend of X that hadn’t been achieved despite Y years of campaigning?

Obviously, it’s good to rehearse your crisis response (you’d expect us to say that). But it’s even more important to translate some of the counter-intuitive logic of what works in modern fundraising into ‘fast facts‘, and perhaps infographics, that your communicators and supporters can use on your behalf when tackling misapprehensions online. Where the issues are foreseeable, be on the front foot by putting this material out ahead of time rather than holding up your social media response and community management activity until a media statement has been crafted. It’s another argument too for human-scale digital channels such as blogs, where you can explain your rationale with a human face, like Macmillan did around the Ice Bucket Challenge in the summer.

Perhaps the lasting legacy of Binkygate will be to make celebrities and their agents more reticent to engage with charities on a paid-for basis. While that may save charities some cash in the short term, if those endorsements really are commercially effective, that may not be a win for them in the long term.