‘The customer is king’ – one of the few maxims that remains unchanging within developed free markets, but social media is fundamentally altering the way in which customers expect to communicate with organisations.

Whereas outward facing channels were traditionally the preserve of the comms team, channels such as Twitter are increasingly being given over to, or shared with, customer service functions; with more and more brands establishing dedicated support handles like @britishgashelp.

The boundaries between customer service and crisis response are blurring, as illustrated by a recent case involving the Travelodge hotel chain.

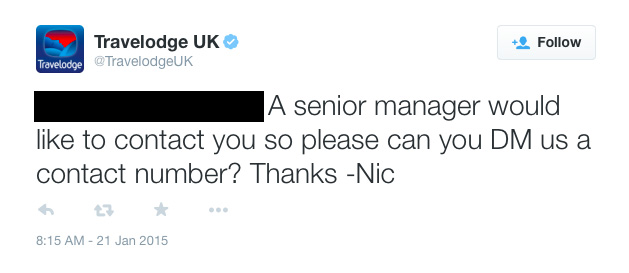

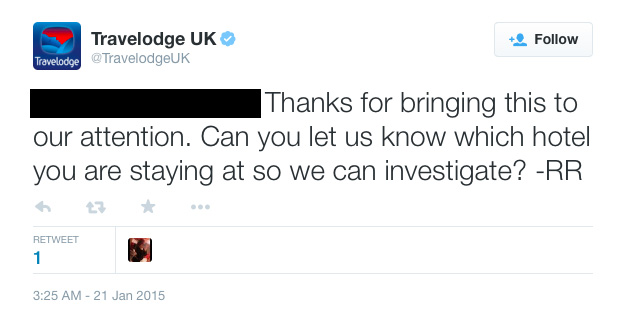

On checking into her hotel room and switching on the TV, a female customer was greeted with the threatening message “I’m going to rape you”; the traditional guest welcome message having been altered by an unknown party. The customer complained to Travelodge via Twitter and was responded to within minutes.

Very quickly, the Travelodge customer team had acknowledged the complaint, gathered details of which hotel the incident had occurred at, and escalated the matter to senior management.

Very quickly, the Travelodge customer team had acknowledged the complaint, gathered details of which hotel the incident had occurred at, and escalated the matter to senior management.

The case was quickly picked up by journalists and, what had started out as a customer service issue, quickly escalated into a reputation-threatening situation for the company, generating national coverage.

As well as presenting exciting opportunities, such as speed and directness of communications – the ‘shift to social’ is having significant implications for the way in which companies prepare for and respond to crises.

Who’s listening?

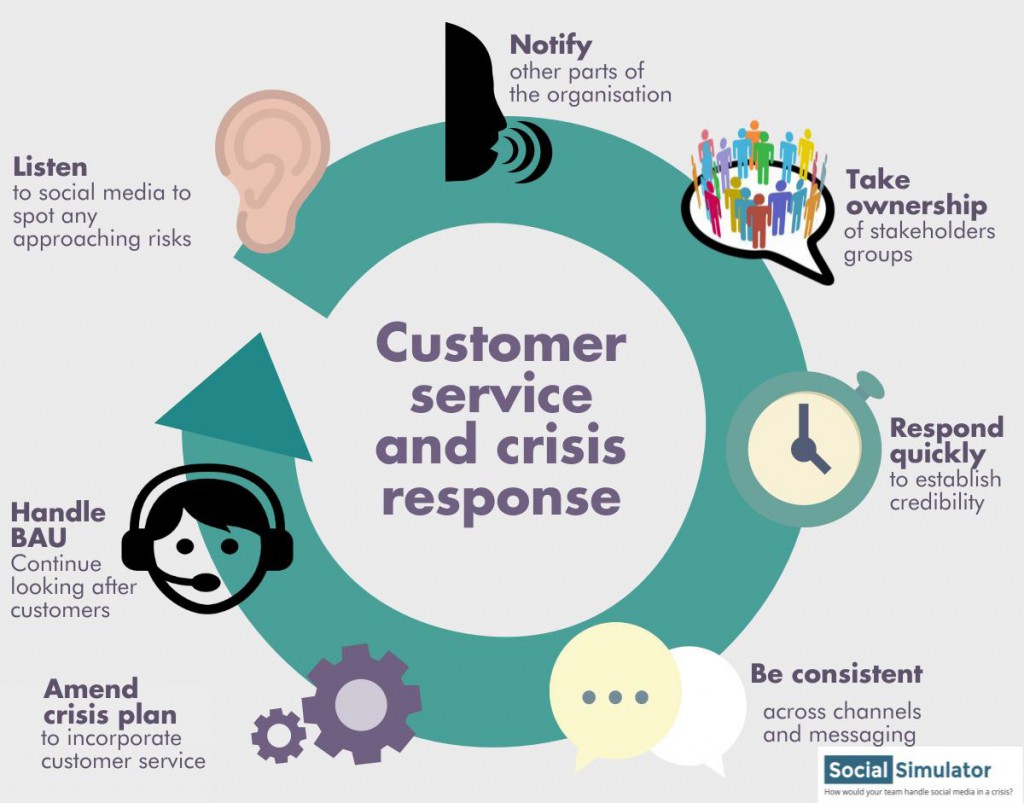

Social media increasingly serves as a trigger for crises. In the case of a crisis that evolves gradually out of an emerging issue, it can also give valuable forewarning that a reputation-threatening situation is developing, but only if an organisation is monitoring the right channels in the right way. Given their ‘ownership’ of social media channels, customer service responders are being increasingly called on to act as the reputation radar for the firm; horizon scanning and alerting and notifying other parts of the response structure to any approaching risk. This crucial role can’t just be improvised – responders need to have an awareness of the organisation’s notification and escalation process; as well as the expectations of their role within it.

Who’s responsible?

The answer to this question depends on the company. Every organisation will have different arrangements in place in terms of which function/s hold responsibility for a given channel. Communications and customer services will often share ownership of a channel; each using it for a different purpose. What is important is that, in a crisis, it is clear which function is responsible for communicating with different stakeholder groups, and that activity is coordinated in such a way that messaging remains consistent across channels and functions. A common pitfall we find with clients is that assumptions can be made that responsibility for engaging with a particular group lies elsewhere, meaning some important influencers can fall through the cracks.

Wait a minute – who’s looking after BAU?

Given that normal business doesn’t just stop in the event of a crisis, there also needs to be a plan for how business as usual queries will be managed alongside crisis response activity.

Why is it taking so long?

The Achilles heal for many a crisis comms response is the time taken for messaging and statements to be approved and signed off by the appropriate parties. This invariably produces bottlenecks, which can give rise to negative perceptions around how a company is managing, or rather – mismanaging – its response. As well as enabling real-time communications, the use of digital channels can add complexity and confusion in terms of what digital responders are permitted to say at a given point in time. A clear process needs to be developed in advance, together with pre-approved policies for messaging and tone, to enable a swift and consistent response.

Fail to prepare…

The bedrock of any crisis response is the crisis plan; the document that sets out how a response will be managed, and who will be responsible for managing which aspects. Given the changing role of customer service agents as frontline communicators and reputation managers on public channels, new plans need to be developed (and existing ones amended) to reflect this shift in responsibilities.

More and more companies are focusing their customer service efforts on social media channels. This is re-drawing the frontline in crisis monitoring and response. This brings challenges, as well as benefits; one of which will be how organisations evolve their existing skills, processes and structures to fit the changing context within which crises are managed.