I had the privilege to see a well-drilled client crisis team at work this week. Their organisation is enormous, and they have a crisis process honed and documented and rehearsed across the world on a regular basis. It’s impressive to witness, with a depth of strategic thought that we don’t often see.

It got me musing on what sets them apart from some of the other teams we work with.

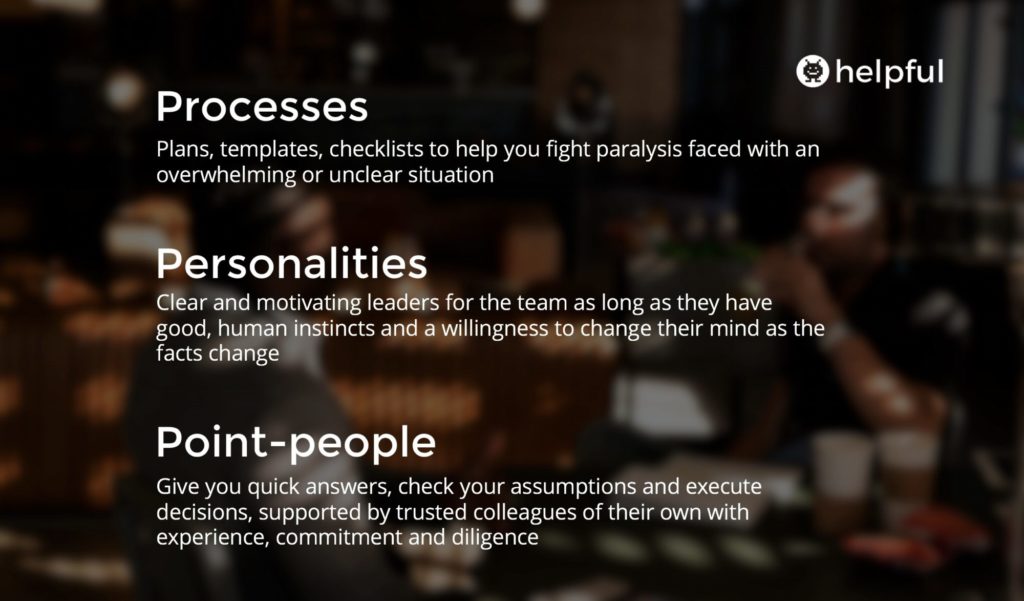

Processes

Most teams we work with have a crisis plan of some kind. They’re often neglected in a real-world incident or even an exercise, but there are documents aplenty. Processes – plans, templates, checklists and so on – help you fight paralysis faced with an overwhelming or unclear situation. They help you remember what you might otherwise forget. But in working through processes you can feel good about your activity while making very little progress. Templates are just a framework after all, and sometimes the time and focus they give you stops you thinking more creatively about possibilities and priorities in a crisis.

Personalities

Personality is often attached to phrases like ‘big’ or ‘dominant’. At first glance, you might think those are the last thing you want around the table in a critical situation. But then without some of those bold characters, you can be left hypothesising and extrapolating, checking and timidly wondering while time ticks away. Like everything, you need a bit of a mix. If your crisis leader is a dominant personality (I’m betting that’s most organisations) they need to learn to chair those crunch meetings inclusively, and be aware their biases and impact their decisiveness can have on daunted junior or quieter colleagues. Hierarchy is a killer in crisis situations. But there’s a lot of value in those big picture, decisive people: if they have good, human instincts and a willingness to change their mind as the facts change, they can be clear and motivating leaders for the team.

Point-people

But charisma and templates won’t fix your crisis. The third vital ingredient – and perhaps the trickiest to set up – is a light but effective hierarchy of people who can work quickly and effectively, with a deep knowledge of how the organisation works and how to find answers under pressure. They’re your point people: and you don’t need hordes of them to be effective. In fact, depending on the situation, you probably really just need a few key people around the organisation who can give you quick answers, check your assumptions and execute decisions, supported by trusted colleagues of their own with experience, commitment and diligence.

While very strong, our client this week hadn’t nailed all three by any means. There were frustrations with the way the templates boxed in their thinking; issues with getting input from everyone in the room with information to contribute; and problems with teams working together to gather information and execute decisions. That’s why they practice, after all. But I suspect when we see them next year, they’ll have tweaked their process, given their big personalities some feedback, and lined up some more of those point people to plug the gaps. And they’ll be in better shape to handle things if they go wrong.